Accounting

Bureaucracy is often deployed keep track of persons, things, money, knowledge, practices, and beliefs. The drive to account arises when an institution or body of knowledge grows to a scale wherein its components need to be documented and counted. Purposes of accounting vary, but the practice shows the power of bureaucracy to also be its weakness: as duties and powers are delegated and disseminated, the need for administration emerges. Administration demands and depends on accounting to make to represent of institutional processes and development, to make them known. This knowledge is embedded in particular forms and formats: indexes, catalogs, lists, two-column entries, and other cross-referencing systems rely on books created to suit the purposes of keeping accounts.

Cora Helen Elizabeth Elliott Account Book

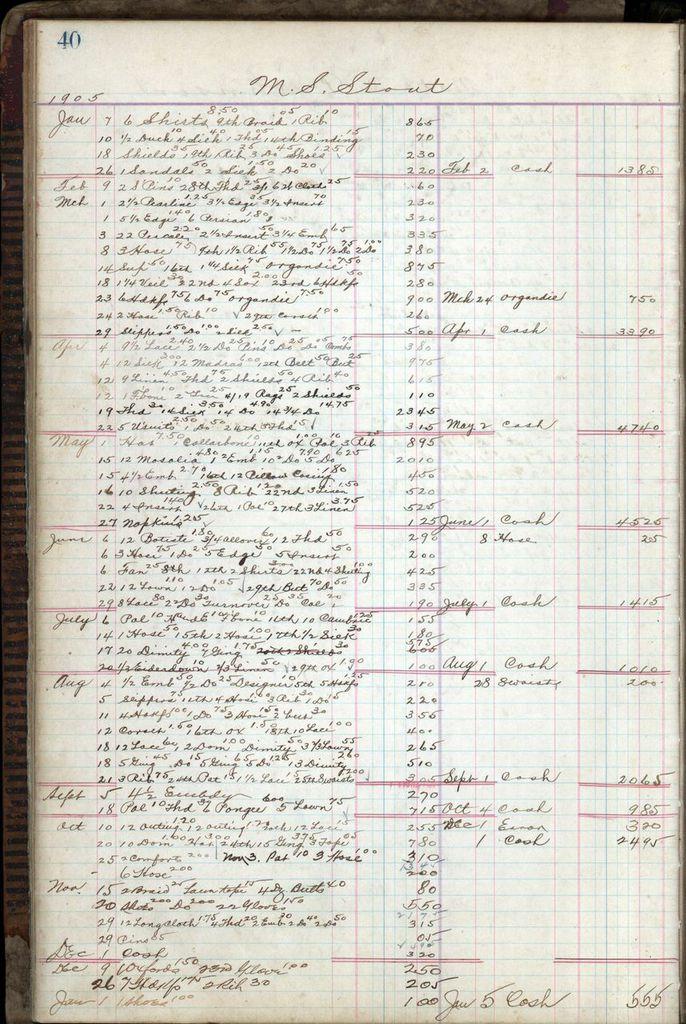

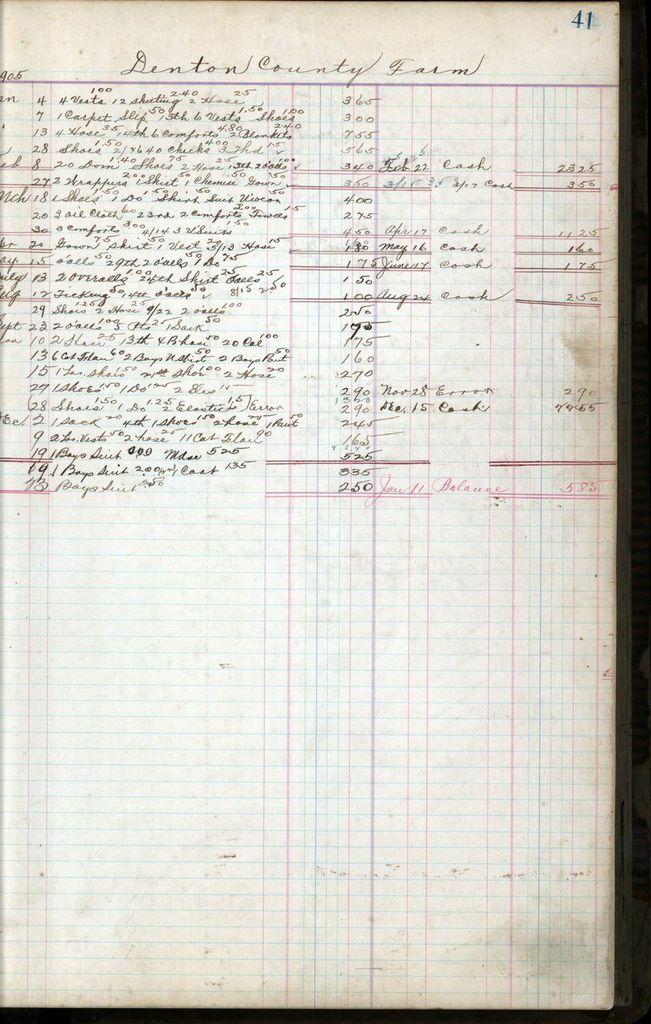

This account book records the activities of a milliner’s shop—a dealer in textiles—operating in Denton, Texas around the turn of the twentieth century. It records, in particular, one year’s activities spanning from late 1904 to early 1905. It was most likely kept by the shop’s proprietor, Cora Helen [Hettie] Elizabeth Elliott. Elliott did business as “Mrs. J. P. Elliott” and documents her personal salary under that name in this volume.

Cora Elliot’s journey to Denton, TX, may be traced to Galveston, TX., in 1880, where her mother, Elizabeth Criss, kept house in the company of her two children: Cora, at that time, and a son, a grocery store clerk. The 1880 Census also shows that Criss rented two rooms in her house, one to a cotton inspector, John [Jacque] P. Elliott from Alabama, and another to a physician, Sam. A. Towsey.

Within one year of the census Cora married Elliott; and, by the 1900 census, the Elliotts had increased in number and relocated to Denton, TX. J. P. and Cora (now registered as Helen P. Elliott) had four children: Mavory [Mabel], Emma Elizabeth, Shada, and, the youngest, a son, Jackson, who would eventually relocate to Los Angeles, California. J. P.’s employment was recorded as that of a “commercial traveller,” and Cora declared herself to be working as a milliner. The book whose pages are reproduced in this digital exhibit are taken from an account book kept by Cora Elliott in the year 1905 for her Main Street milliner’s shop.

While digitization makes it difficult to capture the materiality of the book itself, it is clear that it was a carefully designed artifact manufactured to fit the record-keeping needs of Elliott and others like her. The insider cover explains the construction method:

EVERY SECTION OF PAPER In this book is stitched to a patent heavy woven cloth guard, which is then sewed by hand to specially made extra heavy linen bands, and the entire back of the guards is then reinforced with strong leather, which gives ADDITIONAL STRENGTH, Prevents breaking, and produces a book which opens PERFECTLY FLAT from the first to last page.

As several patent records show, the 1890s saw an interest in the development of record books that would, by design, lay flat without causing damage to the binding, thus preserving the integrity of the collection of individual sheets of paper. The particular example used by Elliott, “The ‘Commercial’ Perfect Flat Opening Blank Book,” was patented in 1894. The patent-holders for “flat opening blank books” licensed various manufacturers to make and sell them. One of the most prominent, and perhaps the manufacturer of Elliott’s book, was The Henry O. Shepard Company of Chicago, Illinois, which won an award for its blank book work at the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Elliott’s book not only lays flat but also provided her with added convenience in the form of a tabbed index, within which she could list her clients by name and cross-reference individual pages of the book, all of which were hand-stamped with an ink page number. Presenting itself with an aspect of seriousness and elegance, the book was embossed on the outside and decorated with maroon paper strips, also embossed with a gold chain pattern. The color scheme of black, maroon, and gold is carried over into the book’s heavy decorative end papers.

Other than the very first, all 472 plus pages of Elliott’s blank book were put to use. Most of the simple semi-calligraphic manuscript writing in the book records individual transactions, arranged in chronological order, under a heading for each client. Notable corporate customers include the Denton County Jail, the College of Industrial Arts (now Texas Woman’s University), First National Bank, the Exchange National Bank, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad Company, and the Texas and Pacific Railway. Most accounts, however, correspond to individuals like Elliott and the members of her family. Each client’s transactions are arranged in a common two-column scheme, one denoting charges for materials received and the other for payments. By consulting these two columns, the book’s user could at any time determine the standing of any client’s bill. Additionally, the book records business expenses, including the cost of merchandise, insurance, freight, and advertising, and sundry expenses including stamps, telephone, envelopes, oil, water, ink, brooms, taxes, coal, rent, soap, telegrams, postcards, lights, “scavenger” services (i. e., street-cleaning and waste removal), towels, laundry, P. O. Box rental, signage, and horse feed, & etc. All told, this account book holds information for transactions between Elliott and hundreds of individuals and groups. The corporate accounts reflect the needs of business. Individual account records reflect how each of these entities used textiles in their day-to-day commercial activities as well as in acts of personal self-fashioning.

Despite its straightforward economic purpose, this book also became a repository of personal, sometimes private, and even highly charged emotional transactions and relationships. “Mrs. J. P. Elliott” is registered as having received $8000 in salary for the year. She also purchased needles and thread, suggesting her work as a seamstress was ongoing while she kept shop. All of Elliott’s daughters had running accounts in the shop. Elliott’s second daughter, Emma Elizabeth, died at age twenty-two near the close of the year that this book documents. Part of her short life is documented on page 380 of this book wherein it is recorded that she purchased three parcels of Liberty silk (produced by a high-fashion London silk merchant and famous for its printed designs), a pair of shoes, and some buttons. Emma’s older sister, Mabel, paid $8.75 for the cost of these materials. The date “Dec 5” is recorded in a slow-moving hand that caused ink to pool at various turns in the formation of the letters. This entry only records a date and no transaction, which is an anomaly in the book’s otherwise remarkably consistent record-keeping scheme. As the 1910 Census records, Elliott had left the milliner’s business by 1910 and reported her employments as those of keeping house and dress making.

This book has been loaned to UNT by McBride’s Music and Pawn, a Denton business on whose current premises this book was found. Dona Terry of Houston, TX, a descendent of Cora Elliott provided important assistance in the compilation of this description.

Index to the Divine and Spiritual Writings of Joanna Southcott

Joanna Southcott (1750-1814) was a self-proclaimed prophetess who began publishing her spiritual and prophetic works in 1801. At the age of 42 Southcott began to hear a ‘voice’ that, she claimed, enabled her to predict various events during the 1790s, including the war with France and food shortages. Due to the accuracy of her prophecies, Southcott quickly drew a number of followers to her cause. Between 1801 and 1814, these followers consolidated into a movement fueled by the volume of Southcott’s publications—over 65 books and pamphlets that circulated in over 100,000 copies collectively (Bowerbank). Published the year after her death, this 240 page book indexes many of Southcott’s popular writings. It is organized alphabetically, and each entry includes a word or phrase, followed by numbers that are assigned to one of Southcott’s works as well as the page number containing the relevant discussion. The book thus functions as a finding aid for those studying Southcott’s writings. However, the book also includes interleaved blank sheets at regular intervals in the text, filled with manuscript notes. These blank pages indicate that the book was also used as a commonplace book in which the reader could copy and compile relevant passages. Generically designed to serve a specific bureaucratic purpose, the interleaved pages and the religious content of Southcott’s works indicate how an index could become a form of spiritual accounting.

Before her visions, Southcott had worked in various households as a maidservant, and her prophetic writings contain an intriguing mixture of prophecy, biblical citation, spiritual advice, and narratives of everyday events from her youth. Southcott appeared to many people as a defender or voice of the working classes in a time of social and political upheaval across Europe and in Britain. Her work could be understood as democratic, but she also developed a practice of “sealing” to attach her followers to her more effectually. “Sealing” was a form of privileged membership approved in a ritualized pledge to Southcott herself; it involved Southcott and her follower signing a paper inscribed with a circle and a message of acceptance, which was subsequently folded and sealed by Southcott (Bowerbank). To be sealed, followers were required to read two of Southcott’s books, Sound an Alarm in my Holy Mountain (1804) and A Caution and Instruction to the Sealed (1807). Southcott’s writings became part of the right of passage demanded of her followers, promoting the development of a devoted and elite group defined by textual knowledge and personal connection to the prophetess.

In this context, we might understand the Index in several ways: as an index, the book opens Southcott’s body of work to a wider audience interested in specific ideas or passages, thus fulfilling the ostensibly democratic bent of her spiritual work. The index also works to legitimate Southcott as an author by drawing on the authority of alphabetically-organized concordances of the Bible, including the standard eighteenth-century concordance to the King James Bible, Alexander Cruden’s Complete Concordance to the Holy Scriptures (1737). The very existence of an index to Southcott’s work confirms the importance of that work by providing an exhaustive account of its content; like biblical concordances, it encourages study and marks Southcott’s writings as not just important but “invaluable” and “inspired” (Cruden, t.p.). As with contemporaneous publications like Joseph Priestley’s Index to the Bible (Philadelphia, 1804), which organizes its content by subject rather than by words and concentrates on prophecy, the Index is designed to enable people unfamiliar with Southcott’s work to navigate it successfully. With the inserted blank pages, the book also provides new readers and the inner circle of her devoted readers with a means of personal inscription, a way of affirming—by copying out her words—their dedication to her cause and work even after her death.

Find Index to the Divine and Spiritual Writings of Joanna Southcott in the UNT Libraries Catalog.

Reports on the State of the East India Company

Private companies funded by individual investors who hoped to turn a profit administered large swaths of the global trade, colonization, and imperial ventures undertaken by early modern Europeans. This was certainly so for the English East India Company (EIC), which was granted a Royal Charter by Queen Elizabeth in 1600. The EIC was extremely successful, and, at its peak, the company maintained a monopoly on half the trade goods in the world. These included cotton, silk, indigo dye, salt, salt petre (potassium nitrate), opium, and tea.

The extensiveness of the EIC operations required it to take on and perform many of the roles normally reserved for sovereign nations and political empires. The Company maintained an active military and defended its activities and possession abroad through force and the threat of force. It also maintained a vast administrative framework backed by an equally extensive communication network. The volume and diversity of the Company’s transactions necessitated enormous record-keeping efforts. As a privately owned and operated Company it looked and acted like a government entity. This blurring of boundaries was exacerbated by the fact that the Company’s vast wealth made it a primary source of borrowed money for the government, which repaid these loans in cash and with its continuing legitimation of the Company’s rights and privileges. In effect, the Company acted as a branch of the government in India and elsewhere. By the early 1770s however, questions began to be raised about mismanagement and misrule.

The pages on display here come from a book (printed in 1804) that reprinted nine reports delivered to Britain’s House of Commons in the years 1772 and 1773. These reports consider the appointment of superintending commissioners in the East Indies; the Company’s financial holdings; the distribution of the Company’s profits gained in the East Indies; abuses by Company servants that diminished profits; the use and account of ships employed by the Company; Company profits and oversight in Bengal; the legal structure employed by the Company in Bengal; a shortage of cash experienced by the Company in England as a result of funds drawn by its servants in India;and the cost of employing Company officers and servants in India. In short, these reports represent a close look into the Company’s financial standing and power structures in an attempt to root out corruption, mismanagement, and an assortment of abuses of power. They also represent a high-profile moment in a series of actions by which the British government sought–and eventually succeeded–to take control of the Company and, in so doing to institute reforms that would address the kinds of problems these reports document. The 1804 date of publication (after the 1787 impeachment of Warren Hastings, the British Governor-General of India and Bengal) attests to the continuing value of these reports as public resources.

Find Reports on the State of the East India Company in the UNT Libraries Catalog.

A Compleat Herbal of the Late James Newton, M.D.

The contents of this printed herbal are based on compilations from earlier herbals made James Newton (1639-1718), a physician and botanist. Newton’s research took him throughout England and the Netherlands and he corresponded with noteworthy contemporary men of science, including Paul Hermann at Leiden, James Sutherland at the Edinburgh Physic Garden, Hans Sloane of British Museum fame, and John Ray, author of the compendious Historia Plantarum (1686-1704). Inspired by the work of these men and others, Newton attentively and meticulously lorded over the realm of botany. Newton’s work aims to fully account for—by name and appearance—the entirety of late seventeenth-century botanical knowledge. An early biographer speculated that botany was a way for Newton, the administrator of a London madhouse, to “divert his attention, in some measure, from the sad objects under his care” (Noble 280). As an imminently rational endeavor, systematically accounting for the universe of plants might have, for Newton, staved off frightful chaos of human minds unloosed from their moorings.

This herbal features images—referred to as “icons” in the Preface—and English names for several thousand trees and plants. This information is organized in 174 tables containing about 20 icons grouped by type. John Ray, whose influence on this herbal is clear, implemented groupings of images by type, which are typical of the Peterson field guides of today. Additionally, each icon is titled with the English names of the plants represented and one or more initials. The initials refer the book’s reader to other botanical texts listed in an opening table. Newton drew much of his information, visual and textual, from these other texts, and, in many cases, the Latin names for the plants are included as part of these inter-textual references. An alphabetical index—also employing the English names of the plants—facilitates navigation of the numerous plates. The order of the plates reflects the progress of the author’s original work as a botanical author. His first book began with grasses and his second, more comprehensive, book began with apples. The contents of both these earlier publications are printed in this herbal, beginning with types of grasses and continuing through, among others, types of horsetails, reeds, corn, beans, peas, lentils, vetches, violets, daffodils, tulips, onions, leeks, garlic, crocuses, turnips, radishes, mustards, rockets (arugulas), endives, dandelions, lettuces, cabbages, beets, ferns, mallows, hollyhocks, apples, poppies, rhubarbs, anemones, foxgloves, carnations, aloes, yuccas, flaxes, potatoes, gourds, pompions (pumpkins), bindweeds, strawberries, mints, hemps, sages, ground pines, marigolds, sunflowers, daisies, thistles, carrots, parsnips, and mushrooms.

Even though this 1752 Herbal was derived from earlier sources, the edition on display here speaks very clearly to its own moment of coming into being. Newton’s son—also named James Newton (1664-1750)—was also a botanist and physician. But his son—that is, the grandson of the compiler of this herbal—entered a different profession when he was educated in Oxford and took a post in the Anglican clergy. This third James Newton arranged for his grandfather’s two seventeenth-century herbals to be printed again in London in 1752, pages of which are reproduced here.

Several motives were at work in the reprinting of these older materials in the middle of the eighteenth century: for one, Newton, the clergyman’s father, had died just two years earlier, in 1750, leaving behind his and his father’s research materials. The publication of this herbal collected these materials and brought them into public view once again in a more comprehensive format. The book’s dedication to Earl Harcourt provides another clue regarding motive: in 1749, the England system of hereditary titles was expanded, with the addition of the titles Earl of Harcourt and Viscount of Nuneham. Both these titles were bestowed upon Simon Harcourt (1714-1777), a British general, diplomat, and Fellow of the Royal Society. As the noble most closely attached to the third James Newton’s church and the village it served, Harcourt made a fitting dedicatee for this book. The herbal would have served as a token of obligation, potentially aimed at ingratiating Newton to this local dignitary; at the very least, it reminded Harcourt of the fact that the Rector of the local church was descended from a line of men of scientific accomplishments.

Two ironic turns close the chapter on the role this herbal played in the relationship between Harcourt and his de facto dependent, Newton. In 1759, Harcourt had the village and church that were Newton’s home and workplace destroyed. This was done to clear land for the building of villa with a carefully landscaped park (designed by the renowned architect, Lancelot “Capability” Brown) for the use of Harcourt and his guests. Newton’s congregation was greatly diminished by this act, even if the park may have provided a pleasant location for the uninterrupted observation of plants. For his part, Harcourt’s ended his busy political and administrative career in 1777, when he retired and took up residence at Nuneham House, built on the site of Newton’s place of worship and work. Within the year of arriving in Oxfordshire, however, Harcourt drowned in a well in an attempt to save his dog that had fallen into it. It is speculated that the destruction of Newenham Courtenay inspired Oliver Goldsmith’s famous poem, The Deserted Village (1770) and its critique of luxury (McConnell).

Find Newton’s Herbal in the UNT Libraries Catalog.