Doing/Making

Even as the material forms of bureaucracy order and fix knowledge, they also convey processes and procedures of knowledge making. Many bureaucratic documents implicitly script a series of actions: filling out, turning in, processing, filing and so on. Reference books, however, explicitly codify how particular kinds of knowledge can and should be made. By detailing how to construct a theater set, how to print a broadside, or how mount a specimen for a museum display, the reference books included here deploy the technical knowledge of the professional to support modern disciplinary divisions.

Encyclopédie

This section of the monumental French Encyclopédie (1751-1780) depicts architectural plans and examples of theatrical machines from the eighteenth century. Each section of the large folio volume begins with detailed descriptions of the plates followed by a set of engravings. The combination of text and illustration reveal the many ways theatres were constructed to enable the creation of specific sets, also pictured in the plates. Chosen because of its historical significance, this set of theater plates reflects the interest Denis Diderot (1713-1784) and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert (1717-1783), the editors of the Encyclopédie, took in describing, systematizing, and disseminating knowledge of the mechanical arts. Diderot was particularly interested in “developing a common language and graphic representation that related words to things through pictorial images” (Pannabecker). The text details the exact construction of various existing theaters and provides precise measurements and locations for trap doors, adjustable frames for scenery, and cat walks; the illustrations show machines for creating wave motion on the stage [Plate XXIII] and for making thunder with a suspended metal sheet [Plate XI]. As was typical of descriptions of scientific experiments in the period, the text-plate combination allows the reader to create the sets and machines depicted, embodying mechanical knowledge as the process of doing and making.

The Encyclopédie was a key text of Enlightenment philosophy in eighteenth-century France; it is often cited as helping foment the French Revolution because of the radical philosophical and political ideas it engendered. Upon its initial publication, the first series was deemed to contain seditious content, leading to the suppression of the first two volumes by the French government in 1752, and suspension of its privilège to print in 1759 by the King’s Counsel (ARTFL). Even though the book was both large and expensive, its popularity continued to grow, and it eventually gained 4000 subscribers. While many of these subscribers were of the educated elite, the project was deemed threatening to the government of France because it placed focus on the common man and advocated for political and social reform. (The descriptions and plates of the mechanical arts were not deemed as controversial as the philosophical sections of the project.) After d’Alembert and his other collaborators quit the project in 1759, Diderot worked tirelessly to complete the remaining volumes of text and plates. He wrote several hundred articles, damaging his eyesight in the process. The last copies of the first volume were issued in 1765. The final volumes of plates were not issued until 1772 and the text underwent a number of revisions and emendations through 1780.

Even as the Diderot resisted the governmental bureaucracy that attempted to stamp out and stop production of the project, the Encyclopédie is itself a bureaucratic form. As a monumental work of systematization, the Encyclopédie participated in the larger eighteenth-century project of cataloguing and synthesizing objects and ideas. As d’Almebert argued in the “Preliminary Discourse,” an encyclopedic arrangement “collects knowledge into the smallest area possible and places the philosopher at a vantage point, so to speak, high above this vast labyrinth, whence he can perceive the principal sciences and the arts simultaneously. From there, he can see at a glance the objects of his speculation and the operations that can be made on these objects; he can discern the general branches of human knowledge, the points that separate or unite them; and sometimes he can even glimpse the secrets that relate them to one another. The encyclopedia is a kind of world map that shows the principal countries, their position, and their mutual dependence, the road that leads directly from one to the other. This road is often cut by a thousand obstacles, which are known in each country only to the inhabitants or to travelers, and which cannot be represented except in individual, highly detailed maps. These individual maps are the different articles of the Encyclopedia and the Tree or Systematic Chart is its world map” (d’Alembert n.p.).

The goal of the encyclopedic project was to provide knowledge seekers with a map to the relationships between different fields of knowledge, but d’Alembert’s metaphor of travelers and obstacles also acknowledges the growing specialization and professionalization that made it difficult for any one individual to grasp the “secrets” that connected all fields of knowledge to all the others. The textual descriptions and detailed plates provided this crucial map in the form of a systematic representation of the tools, methods, and concepts relevant to each field of knowledge. The theatre plates thus enable a person unfamiliar with the inner workings of stage spectacles to understand how theaters worked and to make connections between the theater and other mechanical arts. In broad terms, the plates and descriptions break down each field into its parts and procedures with the ultimate goal of synthesizing all knowledge into a comprehensible whole.

Find Encyclopédie theatre plates in the UNT Libraries Catalog.

Practical taxidermy: a manual of instruction

This late nineteenth century handbook for amateur collectors describes the process of decoying, trapping, skinning, preserving, and mounting animal and bird specimens for inclusion in a natural history museum. The author, Montague Browne, was the curator of the town museum in Leicester, a city in the industrial Midlands in Britain; he was also a member of the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society, a Fellow of the Zoological Society, and the author of The Vertebrate Animals of Leicestershire and Rutland (1889). Practical Taxidermy offers instruction to other museum curators about the preservation and presentation of specimens, but Browne acknowledges the book is “merely an introduction to a delightful art” and does not pretend to convey the “knowledge of anatomy, form, arrangement and color” requisite to the professional taxidermist (viii). Yet even though he positions his instruction manual against the “business” of taxidermy and its “technicalities,” Browne aims to convey instructions for every step in the production of a specimen through his text and illustrations: his directions for skinning a bird, for example, include details of where to place the thumb and how to hold the skinning knife relative to skeletal structure and musculature illustrated in the engravings (93-103). Browne adopts the language and techniques of an emergent profession to train amateur enthusiasts.

The Leicester Town Museum was founded in 1835 by the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society, and was presented to the town in 1849 (Hand-book 3). Town museums in nineteenth-century Britain included displays on various aspects of local history, including flora and fauna. These museums were often eclectic, as collections depended on the generosity of local supporters. In 1864, when the Hand-book to the Leicester Museum was published, displays included ethnological and antiquarian collections (including Roman and medieval remains found near Leicester) and natural history and geological specimens, including a large collection of mounted and preserved British birds and several “specimens of very large fossil Saurians, or Water Lizards, principally from the beds of limestone at Barrow-on-Saur,” a village in Leicester (Hand-book 7). The final chapter of Practical Taxidermy provides directions for setting up a natural history museum along with a fold-out illustration of the “Projected Plan of Arrangement of Vertebrates in the Zoological Room, Leicester Town Museum.” In addition to these plans, Browne surveys a number of other proposed plans of classification that, he contends, are “based on an utter disregard of the requirements of science, leaving out art altogether, and worse still, upon an utter ignorance of the first principles of zoology” (324). As this suggests, the larger goal of Browne’s practical manual of taxidermy was to raise the scientific legitimacy and artistic merit of “provincial” museums in Britain. While courting an audience of amateur collectors, Browne’s instructions for making specimens and displays trade on the bureaucratic and disciplinary structures of both zoological science and the visual arts.

Find Practical Taxidermy in the UNT Libraries Catalog.

American Encyclopædia of Printing

This late nineteenth-century encyclopedia claims to cover all aspects of publishing and printing. As the editor suggests in the preface, “as an Encyclopædia, it aims to traverse the circle of the art to which it relates, and therefore to describe its history, as well as its implements, its processes, and its products” (vii). As part of the Nineteenth-Century Book Arts and Printing History Series, this volume sold itself as a comprehensive resource for use in printing offices, and it thus gave special attention to current implements and processes of printing in the United States (vii). Openly jingoistic in its approach, the editor proclaims the book’s inclusivity: “no class of subjects bearing upon printing, however remotely, has been intentionally excluded” even though the “ever-increasing extension of the realm” of print “added greatly to the difficulty of a comprehensive presentation” (vii). The book opens with a section on “How a Book is Made,” and alphabetically-arranged articles provide in-depth descriptions of new printing processes like electrotyping and lithography as well as general topics like “Paper” and “Proof-reading.” Entries are often accompanied by illustrations that materialize the type of printing described: for example, the plate titled “Printing for the Blind” reads “[t]his Page was composed by Ν. Β. Κηεαςς, Jr. a Blind Printer” and is printed in relief legible to the touch; the page facing the description of “Safety-paper” displays a pattern of multi-colored lines and borders printed on glossy paper designed to prevent counterfeiting. Coupling physical examples of printing techniques with detailed descriptions, the American Encyclopædia exemplifies how printing was done in late nineteenth-century America.

The American Encyclopædia is part of a long tradition of books on the procedures and processes of printing, one that stretches back to the early English printer Joseph Moxon’s Mechanic Exercises, or the Doctrine of Handy-Works Applied to the Art of Printing (1683) and through the printing trade plates included in the French Encyclopédie of Diderot and d’Alembert. Like Moxon’s famous seventeenth-century compositor’s manual, the 1871 encyclopedia tries to cover as much ground as possible while also foregrounding cutting-edge techniques. Its alphabetical organization allowed for easy access to articles—as long as the reader already knew what to look for. As in Moxon’s time and our own, the late nineteenth century had its own peculiar printing jargon comprised of terms of the trade and words reflective of new technologies of production like the “Cottrell & Babcock First-Class Drum Cylinder Press” (129) or the “Dick Mailing Machine” (293) and new products like the “Pettee Patent Envelope” (159) or “Columbier” writing paper (113). The entries reveal how printing defined itself as a profession through bureaucratic means, ranging from patents on machines to publications like the American Encyclopædia itself.

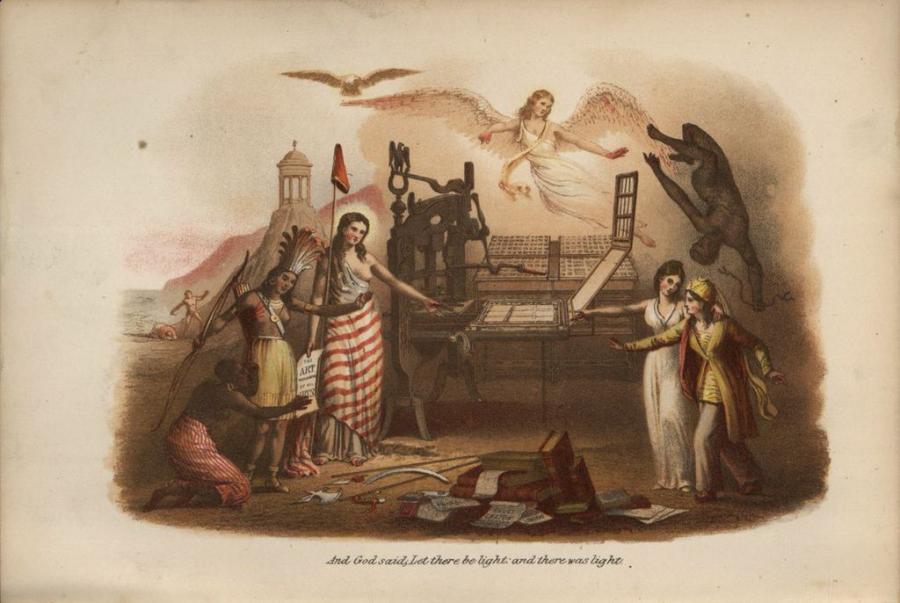

Like many of the books in this genre, the 1871 American Encyclopædia is a celebration of the transformative power of print. The book’s frontispiece “reproduces in color the design of the beautiful vignette upon the certificate of membership issued by the Philadelphia Typographical Society” (viii). The illustration shows a grouping of people of different races and ethnicities gesturing to—and, in the case of the man of African descent, kneeling in front of—a wooden hand press complete with a type case and open frisket. These representatives of the world’s cultures have laid down their weapons of war in front of a pile of books, while a woman representing French liberty holds a printed broadside with the words “The Art of all Arts.” The caption to the engraving reads: “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.” The world-historical importance of printing announces itself in the conventions of high Victorian, Anglo-American imperialism; printing is figured as a civilizing, liberating force on par with the divine power of the Christian God.

Find American Encyclopædia of Printing in the UNT Libraries Catalog.